A railroad requires a lot of regular maintenance to keep the operations running smoothly. And in the old days prior to reliable automotive transport and modern track maintenance machines, a small local maintenance crew would have been responsible for inspecting and maintaining a given section of track of a few miles. The section bunkhouse (and related nearby sheds for storing maintenance supplies, tools and other materiel) served as the home for the local “section” foreman. (These track maintenance workers responsible for a section of railway were sometimes called sectionmen.) With the advent of more mechanized forms of track maintenance, fewer workers could maintain much larger stretches of railway, so manpower needs were reduced, and the section houses closed. Most section houses are now long gone from the railways, but several of the old Algoma Central section houses still stand today. Some stand derelict and abandoned but some (particularly the remaining ones closer to the south end of the railway) are now privately owned camps and cabins.

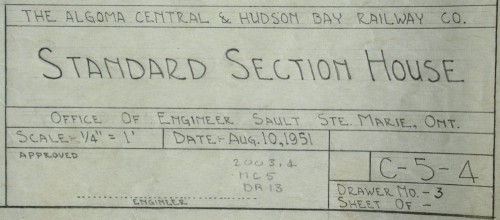

Most railways had standard designs for common structures along the line like section bunkhouses. Here, the Algoma Central was no exception. The ACR’s standard 2 bedroom section house was a 2-story wood-frame structure with the gable ends aligned perpendicular to the tracks, a covered porch at the front and a 1-story kitchen annex at the rear. An original drawing from the Algoma Central’s files of a 1951 version of the standard plan exists in the collection of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library’s archives.

Excerpt from ACR drawing # C-5-4 (Standard Section House). Collection of Sault Ste. Marie Public Library Archives.

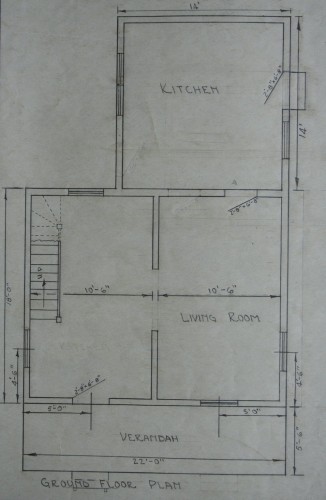

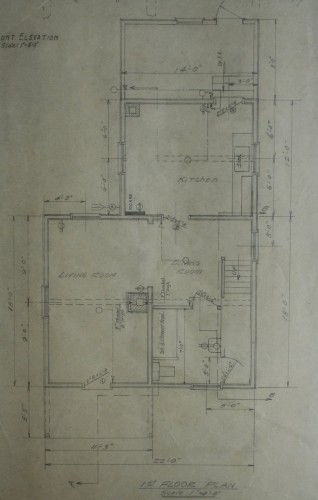

The drawing shows a main structure with and 18’ x 22’ footprint and a 14’ x 14’ kitchen attached to the rear. The main floor features a living and dining area and the upstairs has two equally sized bedrooms. The section houses built along the line tended to vary slightly from the actual drawing though, and a close look at the drawing shows that it’s been revised a couple times and you can see where pencil marks for locations of doors and windows around the kitchen annex have been shifted around on the drawing.

Main floor plan of standard section house.

Excerpt from ACR drawing # C-5-4 (Standard Section House). Collection of Sault Ste. Marie Public Library Archives.

However as mentioned, as new houses were built or rebuilt over the years, the details of each individual section house tended to vary slightly, and I don’t think a single one of the section houses of which I have photographs matches the drawing exactly in every detail. The dimensions of the main part of the structure stayed consistent, but window arrangements could vary slightly from location to location, and sometimes the internal floor plan is mirror imaged from the “standard” plan.

The standard drawings also show a 1/3 roof pitch on the main structure, which some existing houses appear to match (Northland and Franz) but the majority seem to have a much steeper roof pitch, so there’s at least two variations here.

The kitchen annex was where the most variation tended to be; varying in size and particularly in window and door arrangements, much more than the main part of the structure. (It appears that for some older section houses, the annex was actually added later.)

This abandoned but still-standing section house at Agawa (Mile 130.9) is pretty close to the standard drawing (other than some window locations on the kitchen and steeper roof pitch) and illustrates the typical style and finish quite nicely, with an asphalt shingled roof, wide veranda porch on the front of the structure and milled board siding (what Evergreen would call “novelty siding” in their line of textured styrene sheet products for model scratchbuilding).

At Mashkode (Mile 56.2), now a privately owned cottage but more or less unaltered from its previous appearance, we can see the bunkhouse in context of the other outbuildings that would typically accompany the sectionhouse: a small storage shed, and an outhouse.

Not visible, but also would have typically been part of the collection of structures for a section would be a track speeder and tool storage shed near the tracks and in some locations, as the main structure was only a 2 bedroom affair, additional small one man bunk cabins.

Main floor plan of Wyborn section house.

Excerpt from ACR drawing # E-23-4 (Wyborn Section House). Collection of Sault Ste. Marie Public Library Archives.

Often located many dozens of miles from any sort of recognizable community, very few of these section houses were located anywhere near any municipal sources of running water or electricity. Wyborn (Mile 294.1) is a notable exception; the section house here was located within the city of Hearst and an original drawing of this section house also exists in the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library Archives (dated 1937 but with a notation for a 1968 revision), and this drawing shows a full bath with tub and shower on the floor plan, as well as the location of the incoming electrical meter and breaker box (near the left side of the kitchen). This section house is also a little unusual in that instead of a full width veranda porch on the front, there is a simple peaked canopy just over the entry door, and the drawing specifies in this case aluminum siding.

And of course with many of the surviving former section houses on the line now in private ownership as camps and cottages, many of them have been rebuilt to some extent or another, further changing their appearance from the standard plans.

Several years ago, I attempted to build this model of the section house at Franz, scaling it from photos. While the proportions have always felt relatively close, I’ve felt that it ended up being oversize. The dimensions on the original railway drawings confirm that the model is approximately 10% overscale. (I got too-large windows and sort of proportionally scaled things off that comparison.) It’s a pretty good representation, but now that I have access to the proper dimensions in the official drawings, I can do a much better job of constructing a version with much more accurate dimensions.

Hi Chris,

Thanks for sharing the information on section houses. I learned something new about the history of railroading. I am curious though, you mentioned that most of these section houses were isolated away from any communities, so how did the people living there get food and supplies? Would this have been supplied by trains stopping at each section house along the line?

Derek

Hi Derek,

Pretty much the entirety of the Algoma Central ran through remote wilderness with the only major community other than Sault Ste. Marie being the Wawa area which grew up around the mining trade in the early part of the 20th century. So while some sections were located in or near small communities and accessible by road, by necessity the majority of the sections were pretty isolated, and the only way in or out was by rail.

In addition to whatever you can take in on the regular passenger train (which was once daily but now just three times a week and living on borrowed time at that, as local groups have only a few months left before service is discontinued by CN to come up with a way to save the train), the railway once ran a regular wayfreight to supply camps and cabins along the line with freight and materials. I’m not sure what sort of service CN is currently providing, but under Wisconsin Central in the late 1990s this was on a monthly schedule. One of my old Rail Innovations VHS tapes in my collection has a neat little segment on the operation of this train, showing a neat little train with a locomotive, two boxcars (with a third company service/MOW car picked up along the way) and caboose for a rolling office working its way up the line, delivering such items as building lumber, windows, and wood stoves at remote stops along the line.

Thanks for the detailed reply Chris. Its interesting what it took to keep a railroad running in the past before all the hi-rail vehicles and MOW rail vehicles that the railroads use today. Especially in remote areas like northern Ontario with no other access but by train.