Today I got a package in the mail from my dealer containing one of the new Rapido FP9A locomotives factory decorated for Algoma Central #1750. Acquired by WC in 1995 for the ACR passenger trains, it’s a little completely out of my era, but I just “had” to collect a couple of Rapido’s models to put together a “modern” (1995-2000) version of the ACR’s regular passenger train. It’ll mostly reside on a display shelf, but be fun to run through every once in a while.

In the box, with solid protective packaging.

The model comes packed in a protective plastic holder that securely wraps around the engine and holds it tightly, and did a good job of protecting it from any damage in shipping. Every little bit and piece appeared to be completely intact.

Additional parts bag.

Little parts baggy including extra re-rail frogs, steam line connections and extra couplers and a part for a rear diaphraghm. The AC units didn’t have them (and neither did the majority of the old CN units, and many that did had them removed later), so that piece won’t need to be installed.

The model, out of the box!

Here’s the model taken out of the box and set on the rails of my in-progress switching layout. You’ll have to excuse the background and the quality of some of these photos; this small layout isn’t very finished and the lighting in this room isn’t the best.

The real 1750 arriving at Steelton Yard on the head of the southbound Agawa Canyon Tour Train. Blair Smith photo, August 1996.

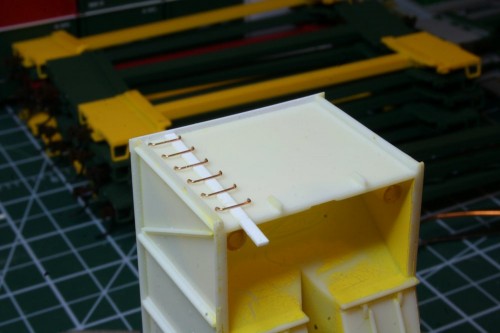

Winterization hatch detail, with stack extension.

The model has a lot of gorgeous detail, although a couple of things stuck out. On the large winterization hatch over the radiator fans, there’s a tall exhaust stack extension which doesn’t appear to have been present on the AC units. This may have been applied at some point in the past to the CN units that eventually (by way of VIA) became AC 1750 and 1751, but weren’t there under ACR ownership. Fortunately with a bit of firm but careful pressure, this stack extension can be pulled out. The hatch also doesn’t appear to be quite fully seated all the way down on the close side, but this should be fixable.

Rear detail, also showing exhaust stack extension removed. The back-up light to the left of the door lights up when the engine is set in reverse.

Since I got the DCC/Sound version, naturally I wanted to get the locomotive fired up on the NCE PowerCab I’m powering the switching layout with. At first – nothing happened. I checked the manual with the model, and the text indicated that the decoders are set by default to address “3”. (3 is the standard default address for a decoder, but I kind of expected the installed decoder to be set to the model’s road number in this case. No big deal, reprogramming a decoder address is a pretty standard task.) Once I was able to select and send a command to the engine, a quick tap of the F8 function key on the throttle (Function 8 is the standard mute/un-mute function for most sound decoders) brought the sound to life. The sound sounded quite agreeably like the EMD 567 engine in the FP9, which it well should – Rapido has a couple of videos on their YouTube channel of their antics in recording the actual sounds off a pair of real FP9s on a tourist railroad in the US. The sound volumes will probably eventually be adjusted down, but aren’t nearly as loud as many other sound decoders are on their factory settings, which usually seem to be set to “max”, when 25-50% level would probably sound much better.

I haven’t quite finished the points on several switches on this layout, so I was only able to run the engine back and forth about a foot or two. It seemed to run reasonably well (although it was a little jerky on speed step 1, but smoother on step 2), and the sound revved up and down nicely, but I think I’ll need to take it out to the club layout sometime to really give it a good breaking in.

The engine has some nice lighting functions as well. Headlight and ditch lights are independently controllable, as are the class lights and numberboard lights (although the numberboards end up being just about as bright as the headlight). The headlight, ditch lights and numberboards appeared to have a slight greenish tint to them, when I’d prefer a more “natural” incandesant-looking warm yellow. Note sure yet if I’ll look at possibly replacing the LEDs used.

Powered up with headlights, ditch lights and white class lights lit. Numberboards are also able to independently light up, but turned off in this photo.

The class lights lit up nice and bright white; the instructions indicated that the F10 function should switch them between Off, White and Green, but I seemed to only be getting them rotating between Off and White. No green. Not sure if I did something wrong, or if it’s something in the programming setup of the decoder, but it’s not too likely that I’ll ever be running this particular unit on the head of a train with additional sections following.

(Edit: Jason from Rapido pointed out in a comment that the decoder on this model is changed and the white and green lights are separately controlled on F10 and F11. This was actually indicated on a technical reference insert sheet for the decoder, which I hadn’t closely read at the time as I didn’t realize the functions would be mapped differently from the information in the original instruction manual for the FP9s.)

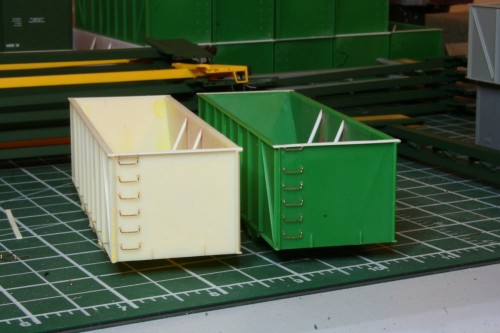

A full set of Rapido Algoma Central passenger equipment: FP9A locomotive, steam generator car, baggage car and coach.

The silver paint on the locomotive is a good match to the shade used on Rapido’s previous offerings: the steam generator car, baggage car and second run of coaches (the original run of AC coaches came out in an odd tan colour, which was changed for the later run(s)). With one of each, it makes a nice solid train.

The lettering and decoration looks pretty good. The model does not have the reporting marks and numbers on the sides near the rear – these were added a little bit later, not when they were originally painted, so it’s not inaccurate, although the units would have spent more of their lives with the numbers than without. So it might have been nice if the side numbers were included, or if a small decal sheet with the numbers was included so modellers could choose. Since I actually model the 1980s, I’m not running this set as any particular year, but it is something that some might wish to note.

—

Postscript:

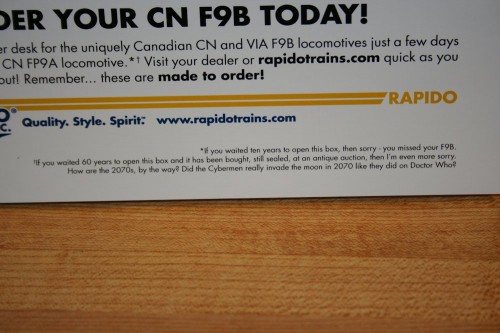

Included in the box was a flyer for Rapido’s upcoming CN/VIA F9B models. The fine print at the bottom is a classic example of the geeky institutional humour brought by Rapido’s founder and owner, Jason Shron:

Always read the fine print…